Inside the Catalogue | With The Archivist

Sitting down with Catherine Sidwell, Senior Design Archivist at Morris & Co.

22 May 2023 -

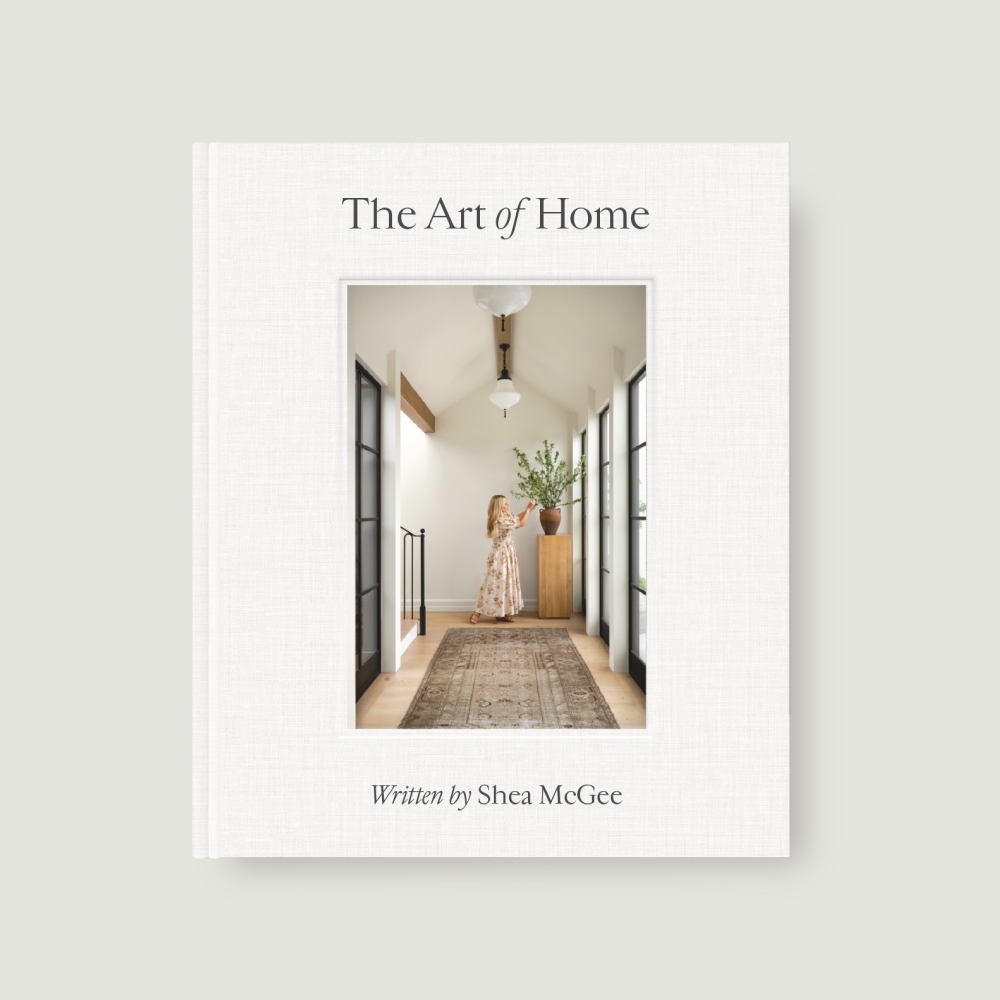

As a British textile designer, publisher, environmental campaigner, poet, and artist, William Morris (1834–1896) was one of the single most influential artistic figures of the nineteenth century. Under his direction, Morris & Co. grew to the status of Arts & Crafts icon that it remains to this day. Catherine Sidwell, a Design History PhD graduate, and expert in the intersection between nature and interior design, has brought her vast knowledge of patterns, fashion textiles, and wallpapers to this iconic brand as their Senior Design Archivist. In this exclusive conversation, as you’ll find in McGee & Co.’s summer catalogue digitized below, Catherine reveals how powerful pattern can be in both expressing who we are, while simultaneously cultivating our love for home.

What was the inspiration behind Morris & Co—the person, the patterns, and the history?

William Morris was inspired by nature. He grew up in the north of London at Epping Forest. As a boy, he wandered around the forests and loved being amongst the trees. There was an Elizabethan house nearby with tapestries, and nature was abundant. I think he took inspiration from nature, and how historically nature’s been represented. He studied patterns, and he was interested in the history of handcrafts, not just in Britain, but he respected the history of crafts from across the world.

Tell us more about the Arts & Crafts Movement.

The interesting thing about the Arts and Crafts Movement is that it grew out of a response to represent nature in a naturalistic way. The French were representing nature almost botanically in their walls or on fabrics. Morris led the way in trying to create flat patterns for interiors. You can represent nature, but it shouldn’t look directly like nature. It can be reminiscent of or remind you of nature, but not in a botanical way. He had many followers outside of the Arts and Crafts Movement, which was only serving a really narrow section of society initially.

The Arts & Crafts movement seems to have experienced a modern resurgence. Why has it seemingly always held an important place in design?

Fashions come and go, and sometimes fashions in interiors are all about new things. In the 21st century, life is so fast-paced in cities and towns, and we’ve lost our connection to the countryside, our roots, and changes in the seasons. If we’re living an urban life, by decorating with Arts & Crafts patterns we’re giving ourselves a daily dose of nature. The patterns are restful and the colorways relaxing. So even if we’re living in an urban setting in a world city with a bustling environment outside the front door, or existing with the world of social media, we can gain respite by being surrounded by these beautiful patterns. I think that’s why the resurgence has occurred. But it doesn’t feel like a fashion blip to me, it feels like something lasting—because I think today, when there is very little handcraft, we really respect the work of those people so long ago.

What other design trends have changed or carried over from time and space? And how do these trends affect the personality/life of a space?

When I studied my Ph.D., I was part of the Modern Interiors Research Center. So, I think a really important thing to speak about is the way that rooms have evolved over time. Houses were built initially with a big entrance wall and then a corridor with rooms off it. Rooms were compartmentalized and the sexes were separated. There might be a drawing room where people would spend time or you’d entertain your visitors, and a dining room, which was more dramatic—like Morris’s dining room, a bit more theatrical. The nursery would be tucked away, and you would have your servants in the kitchen. You wouldn’t sit in the kitchen, but in the dining room to eat. I think it’s important to think about how those spaces have become much more fluid and open over time. Now, we’re living in rooms where we cook, eat, entertain, hang out with our family and friends. And that’s a different situation. I think that wallpapers and textiles give those spaces personality. Today, it’s an arena for expressing one’s personality or for creating an atmosphere that’s conducive to relaxing.

How do you feel that archival designs influence more modern patterns or crafts? Obviously, you’ve spoken about nature, that seems to be a common thread that continues over time and kind of harkens back to history. Are there other patterns or styles that have influenced today’s patterns that you’ve noticed?

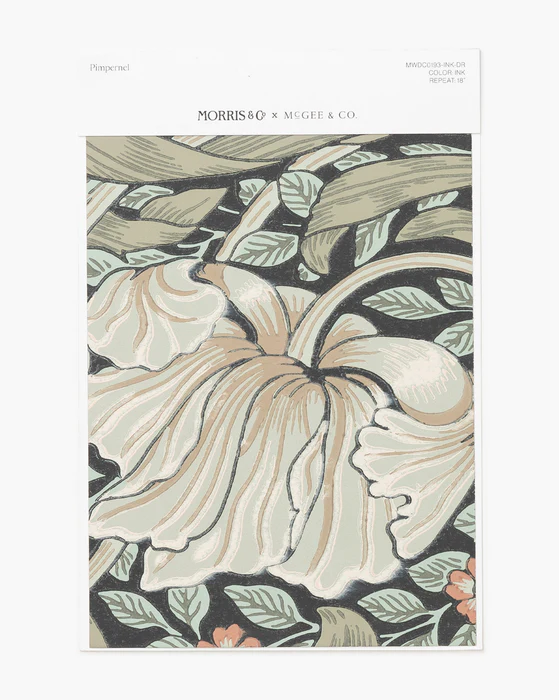

When researching decorative designs for the domestic interior, designs can be categorized. So first and foremost there are florals, and then second there are particular motifs that repeat again and again. Historically, there were things like flowers and baskets, or flowers and ribbons, or ribbons and bows, or the structure of the pattern might be a floral trail, a trellis pattern, or an OG pattern. There’s often a structure behind the pattern and then there can be particular motifs that repeat. Here in England, exotic flowers used to be most popular, but then Morris brought the humble countryside flowers, or garden flowers, into patterns. I love how he names patterns often by the smallest flower. So, Pimpernel, with those enormous tulips, is named after the tiny flower, in the countryside here, rather than big exotic blooms.

It’s the flowers, flowers and insects and birds, and then animals. Then, periodically, different cultures inspire patterns as well. And in Britain, who had a big empire historically, they were drawing inspiration from across the world because they were trading with so many different countries. The Scottish Paisley is from here, but they started producing textiles with the paisley pattern in India which was then sold back to Britain. That’s the thing about trade. We sometimes think that things are very British, but they actually come from across the empire, from hundreds of miles away. And as soon as the Silk Route was operational, that was a way—a method, a media—for certain different patterns to move through countries and then be picked up in other countries. It’s such a great reminder again of the history, the depth and breadth, of patterns and things we take for granted because we see them—but when you stop to really think about their origin, it’s vast, and it’s fascinating. And you know, whether it’s architects or musicians, everyone’s gathering things, and then they process it, or dream about it, or think about it, and it can be realized in all sorts of ways.

“Ensure that you have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” What does this quote by William Morris mean to you in relation to the beloved relationship one has with their home?

I think in order to understand that quote, you need to look at some of the really overstuffed, mid-Victorian interiors where there’s hardly any breathing space. It’s like a chock a block full of lots of different materials. The mantelpiece is stuffed with ornaments, there are pictures everywhere. There’s fabric upholstery, there are cushions, there are drapes. If you imagine William Morris as a young boy growing up and seeing those interiors, there’s not a lot of breathing space. And he loved being out in nature in the countryside where there was space. Actually, medieval interiors didn’t have all that paraphernalia. The floors, timber, oak paneling, some tapestry (which served as decoration and warmth), some wooden chairs, and perhaps a tapestry cushion, were very simple. If you look at Morris’ interiors, they’re very similar to those medieval ways of decorating. I think part of it also was about not having excess and living in a simpler way. And I really love that it’s useful or beautiful to have vessels or things that feel good or are really functional. That’s why I went to study design history. I was always fascinated by people’s responses to certain shapes or certain things. And when you handle something that works well or performs really well, there’s a joy in that, in addition to there being joy in looking at pattern or feeling textures. I think it’s a beautiful motto for the home. If you think now, people with clutter have storage units because the house is bursting. Lots of people in England have garages, but there’s no space for a car. They’ve just got so much stuff. So, in an age of decluttering or wanting a more restful home environment, it’s a motto, and it’s a great motto, to live by.

How does one become a senior archivist?

I’ve always been fascinated by patterns and how people decorate their interiors, and I discovered I could study a degree called Design History—it’s like Art History, but it’s about science. I absolutely loved studying it, and from that, I went on to know that I wanted to be a curator working in museums and galleries, working with historic collections. But I was also really fascinated by Laura Ashley’s patterns when I was growing up and the fashions. I’ve long had a keen interest in fashion and textiles and wallpapers. This led to me working freelance as a journalist, writing about design, culture, and nature. Then I studied a Ph.D. about the representation of nature in the domestic interior from 1851 to 1914 and knew I wanted to write about the Arts & Crafts Movement. I wanted to look at the work of Morris and C.F.A. Voysey. He was a man 20 years younger than Morris, and both were seen as great pattern designers. I came to look at the collection here when I was studying in 2016 and really enjoyed my visit. When the role of Senior Archivist came up, I applied, and I’m thrilled to be here. It feels like all the things I’ve done before have come together and I’m now just thrilled, really thrilled to be here.

Is there a pattern that is your favorite? I know that’s not unlike asking a musician if they have maybe a favorite song, but is there a print or pattern that you feel especially connected to?

You know, I don’t think I can single one out, and that’s a real shame. I think I appreciate them for different reasons. The willow boughs, for example, is a really iconic design, and I love that design because William Morris’s daughter wrote about plants and observed birds in great detail, sort of like a naturalist would. He studied the leaf and he’d point out to her how it curled. And when you look at that pattern you can see it was designed by someone who really studied the essence of how a willow is. That really moves me emotionally, it does. I’m from a family of observers. We notice things that other people don’t seem to notice, and we’ll be standing, talking to each other, and then say, “oh, you know, listen to that robin,” or “have you seen what the blackbird’s doing over there?” We look in that way. We’ve got an eye that is interested in those things. And when I see his designs, but with willow boughs in particular, you know someone has carefully observed the willow trees along the Thames, just as there are at Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire.

He would have seen these trees daily, and then put his environment into practice. I feel almost tearful talking about it. But it’s gorgeous, it’s really gorgeous. I think that’s why we appreciate it. We know what is being represented. We have had experience of it, and I think that’s why it feels really engaging. He’s just such a master of pattern. I don’t think there’s a single pattern that doesn’t work.

When we open the drawers here, when we’re looking in the archive, we’re all gasping and shaking our heads and saying, “I really love this design.” And then you turn and look, “oh, I really love this!”

How do you personally feel about this McGee & Co. collaboration? Seeing the historic patterns of Morris & Co. reimagined in new, exciting, and exclusive color palettes for McGee & Co.

I really love it. I really love that when people discover his patterns, there is often a very strong response, a strong emotional response. I love that Shea found this William Morris wallpaper that had been lying around for a while, not sure what to do with it, and then an opportunity arose. And it looks so sensational. I have to confess that I’ve now suggested my mum uses Pimpernel in her bathroom, in a colorway that tones with what she has. I would never have thought to put Pimpernel in a bathroom, but I’ve been bothered by her bathroom. I’ve just been thinking, “this bathroom needs something.” So, after seeing how Shea used it, I thought that the Pimpernel pattern would look sensational. No, I do, I really love it and I think that’s what makes my job here so exciting. As a museum curator, often it’s sharing knowledge about the history and the artifact exactly as it is. Those things are revered because they’ve been kept, and it’s all about keeping that for the future so that people know what was done historically. So, when people externally come to work with us or have an idea of how they’d like to interpret patterns, it’s taking those designs and extending and opening up their life. That’s why I’m so thrilled about being here. It’s great. I love that. I think it’s such a beautiful opportunity to share these beautiful, historic patterns to a new audience, and I think they will be inspired to look at their spaces with new eyes and hopefully see new opportunities.

Inside the Catalogue | With The Archivist

Sunflower Porcelain Wallpaper

Arbutus Indoor/Outdoor Pillow

Marigold Umber Wallpaper

Willow Pillow Cover

Pimpernel Ink Wallpaper

Sunflower Pillow Cover